The Atlantic's Ta-Nehisi Coates spent seven weeks this summer at an immersion French course at Middlebury College:

I was there to improve my French. My study consisted of four hours of class work and four hours of homework. I was forbidden from reading, writing, speaking, or hearing English. I watched films in French, tried to read a story in Le Monde each day, listened to RFI and a lot of Barbara and Karim Oullet. At every meal I spoke French, and over the course of the seven weeks I felt myself gradually losing touch with the broader world. This was not a wholly unpleasant feeling. In the moments I had to speak English (calling my wife, interacting with folks in town or at the book store), my mouth felt alien and my ear slightly off.

he majority of people I interacted with spoke better, wrote better, read better, and heard better than me. There was no escape from my ineptitude. At every waking hour, someone said something to me that I did not understand. At every waking hour, I mangled some poor Frenchman’s lovely language. For the entire summer, I lived by two words: “Désolé, encore.”

From this he examines scholastic opportunity and achievement, how different ethnic groups approach intellectuals in their midst, and class conflict in general, as only Coates can. It's a good read.

Jim Angel, the Illinois State Climatologist, wrote yesterday that Chicago-area precipitation seems to have shifted around 1965:

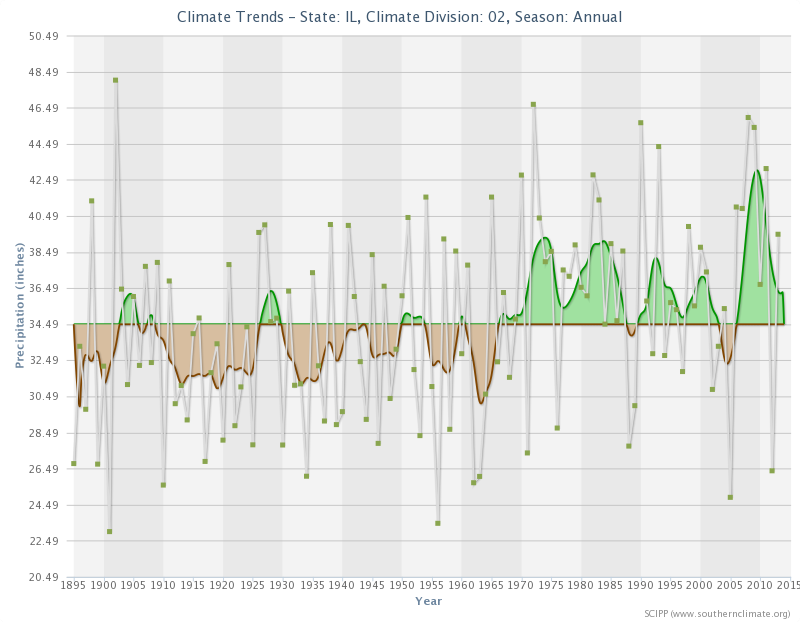

First of all, northeast Illinois (Cook and several surrounding counties – see map below) has experienced a shift in precipitation over the last 120 years. This plot shows the amounts for each year as green dots, and an 11-year running average showing longer periods of dry conditions (brown) and wet conditions (green). There is a pretty remarkable shift from a drier climate between 1895 and 1965 with lots of brown, towards a wetter climate from 1966 to present where green dominates.

If you compare the average annual precipitation between the two periods, you get 836 mm for the earlier period and 935 mm for the later period. That is a 99 mm increase, or about 12 percent.

Of course, we have still experienced drought conditions in this later wet period, as noted in 2005 and 2012. However, the wetter years far outnumber the dry years since 1965. BTW, this pattern is not unique. I have seen this across the state.

So, with slightly warmer weather, milder winters, and more precipitation, it looks like Illinois might suffer less from climate change than other parts of the country. However, those conditions have led to increasing insect populations and more-frequent large precipitation events, with non-trivial costs.

At least we're not in South Florida, which not only faces complete inundation from rising sea levels, but also a climate-denying Congressional delegation.

He thinks we should all use GMT instead:

[W]ithin a given time zone, the point of a common time is not to force everyone to do everything at the same time. It's to allow us to communicate unambiguously with each other about when we are doing things.

If the whole world used a single GMT-based time, schedules would still vary. In general most people would sleep when it's dark out and work when it's light out. So at 23:00, most of London would be at home or in bed and most of Los Angeles would be at the office. But of course London's bartenders would probably be at work while some shift workers in LA would be grabbing a nap. The difference from today is that if you were putting together a London-LA conference call at 21:00 there'd be only one possible interpretation of the proposal. A flight that leaves New York at 14:00 and lands in Paris at 20:00 is a six-hour flight, with no need to keep track of time zones. If your appointment is in El Paso at 11:30 you don't need to remember that it's in a different time zone than the rest of Texas.

Sigh.

It's even easier to get people to use International System measurements than to get them to understand the arbitrariness of the clock, but let's unpack just one thing Yglesias seems to have missed: the date.

Imagine you actually can get people in Los Angeles to use UTC. Working hours are 16:00 to 24:00. School starts at 15:45 (instead of ending then). In the summer, the sun rises at 12:30 and sets at 02:00.

Wait, what? The sun sets at 2am? So...you come home on a different day? That makes no sense to most people.

Yes, in a world where people are unwilling to give up their 128-ounce gallons and 36-inch yards in favor of 1000-milliliter liters and 100-centimeter meters, a world where ice freezing at 32 and boiling at 212 makes more sense than freezing at 0 and boiling at 100, a world where Paul Ryan is thought to be a serious person, we're not moving away from the day changing while most people are asleep.

And don't even get me started on the difference between GMT and UTC.

One hundred years ago today, just a few kilometers from where I'm now sitting, Cleveland installed the first electric traffic signal at corner of Euclid and East 105th:

Various competing claims exist as to who was responsible for the world's first traffic signal. A device installed in London in 1868 featured two semaphore arms that extended horizontally to signal "stop" and at a 45-degree angle to signal "caution." In 1912, a Salt Lake City, Utah, police officer named Lester Wire mounted a handmade wooden box with colored red and green lights on a pole, with the wires attached to overhead trolley and light wires. Most prominently, the inventor Garrett Morgan has been given credit for having invented the traffic signal based on his T-shaped design, patented in 1923 and later reportedly sold to General Electric.

Despite Morgan's greater visibility, the system installed in Cleveland on August 5, 1914, is widely regarded as the first electric traffic signal. Based on a design by James Hoge, who received U.S. patent 1,251,666 for his "Municipal Traffic Control System" in 1918, it consisted of four pairs of red and green lights that served as stop-go indicators, each mounted on a corner post. Wired to a manually operated switch inside a control booth, the system was configured so that conflicting signals were impossible. According to an article in The Motorist, published by the Cleveland Automobile Club in August 1914: "This system is, perhaps, destined to revolutionize the handling of traffic in congested city streets and should be seriously considered by traffic committees for general adoption."

Only 100 years later, the traffic lights have minds of their own.

From my hotel room right now I can see the A-concourse at Cleveland Hopkins Airport about 500 m away. Between here and there is a parking lot and the terminal access road. The setup isn't fundamentally different from the location of the O'Hare Hilton, except a few trees and traffic levels. Oh, and the walkway.

The O'Hare hotel connects directly to all three terminals via underground walkway as well as surface paths through or around the parking structure. In other words, a traveler can walk from his plane to the O'Hare Hilton directly, without taking his life into his hands.

Not so here. Look (click for full size):

If you walk along the terminal access road, you run out of sidewalk by the first curve. Somehow there's a path through the parking structure, but again, once you get to the edge of the parking lot southeast of the structure, you're climbing through sod and ground cover to get to the hotel's ring road.

Still, I did it last night, and from my gate to the hotel took 17 minutes. Last time, when I waited for the hotel shuttle bus, it took twice as long. Fortunately it didn't rain either time, but if it had rained, waiting for the shuttle bus would have been damper.

Now I've got to catch the rental car shuttle, which picks up back at the terminal, so I'll have to pick my way across the parking lot and parking structure until I find a way though to the pick-up spot. Because no one wanted to build a sidewalk to bridge the one-block chasm between the hotel and the airport.

Related: NPR reported this morning that our food intake hasn't changed in 10 years; we're all getting fat because we don't walk enough.

As a big Jane Jacobs fan, I'm very happy to learn that the FBI's ugly headquarters in Washington may be demolished soon:

This week came the news that the Federal Bureau of Investigation is leaving its home in Washington, D.C. While plans to keep the bureau downtown were always a longshot, a short list of candidates released by the GSA confirms that the FBI will build a new consolidated headquarters in either Maryland or Virginia. Washingtonian spotted the release and wasted no time in celebrating the FBI's departure—despite the fact that the move will send as many as 4,800 jobs to the suburbs.

That's how much D.C. residents hate the J. Edgar Hoover Building. And really, that doesn't come close to painting how passionately people hate this building.

Yeah, because it's a really ugly building.

The Atlantic's Kriston Capps, who wrote the linked article, worries that its replacement will be bland, and therefore maybe we don't want to tear it down? No. Tear it down. And worry about the replacement building during its design phase.

The Brutalist period was so called for a reason.

Client deliverables and tonight's Cubs game have compressed my day a little. Here's what I haven't had time to read:

Now back to the deliverable...

Downloading to my Kindle right now:

...and a few articles I found last week that just made it onto my Kindle tonight.

Oh, and I almost forgot: today is the 80th anniversary of John Dillinger's death just six blocks from where I now live.

For once I'm not ranting about politics. No, check out these spite houses:

About a century ago, a Bay Area man named Charles Froling was just learning that he wouldn't be able to build his dream house. An inheritance had gifted him a sizable chunk of land, but municipal elders in the City of Alameda had decided to appropriate most of it to extend a street. So Froling sadly rolled up his blueprints and murmured, "Ah well, that's life."

No, of course he didn't do that. Having a constitution made from equal parts righteous indignation and pickle juice, the frustrated property owner took what little land he had left and erected a stilted, utterly ridiculous abode. The house measured 54 feet long but only 10 feet wide, as if a tornado had blown away two-thirds of the original structure.

They have art. I can't tell if the houses depicted are cozy or horrifying, though.

This map surprised me:

Max Fisher explains:

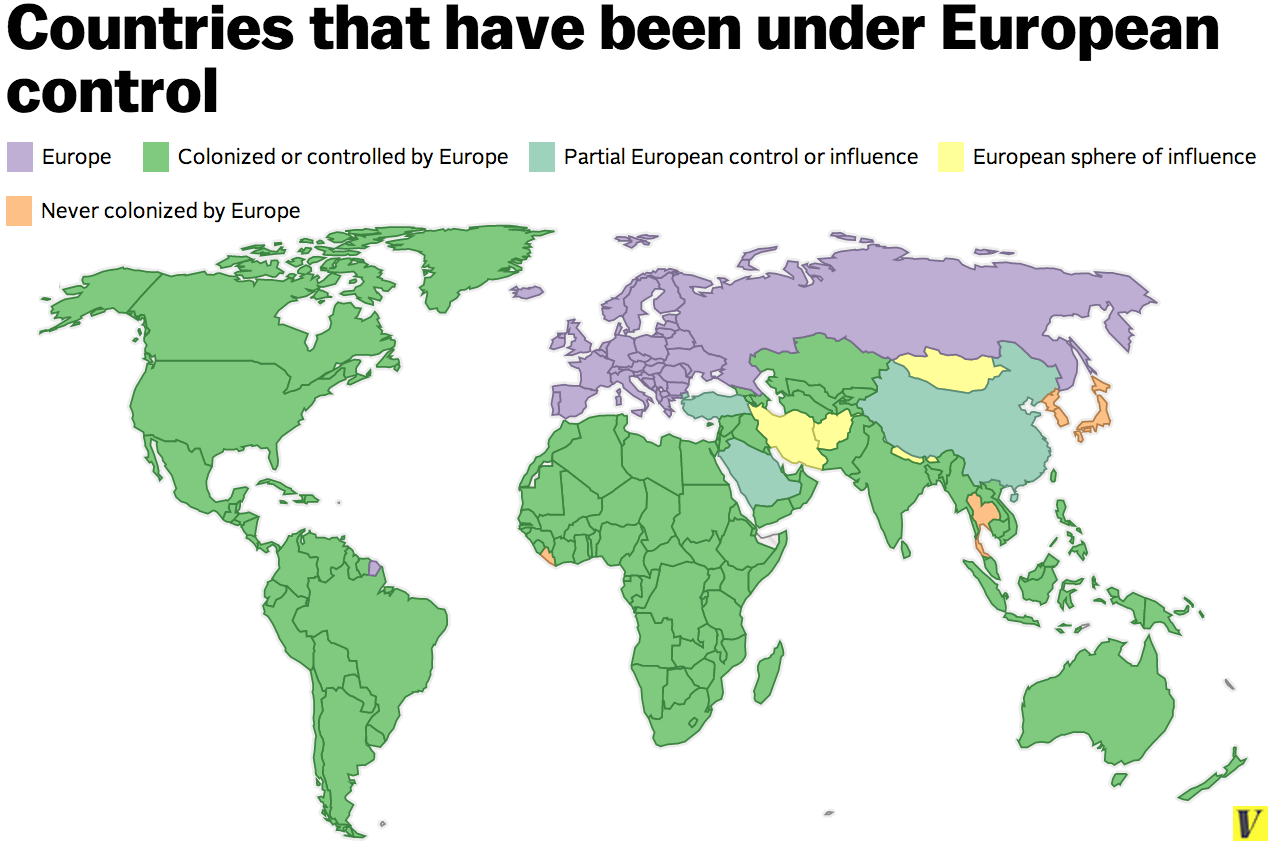

It's no secret that European colonialism was a vast, and often devastating, project that over several centuries put nearly the entire world under control of one European power or another. But just how vast can be difficult to fully appreciate.

Here, to give you a small sense of European colonialism's massive scale, is a map showing every country put under partial or total European control during the colonial era, which ran roughly from the 1500s to the 1960s. Only five countries, in orange, were spared:

There are only four countries that escaped European colonialism completely. Japan and Korea successfully staved off European domination, in part due to their strength and diplomacy, their isolationist policies, and perhaps their distance. Thailand was spared when the British and French Empires decided to let it remained independent as a buffer between British-controlled Burma and French Indochina. Japan, however, colonized both Korea and Thailand itself during its early-20th-century imperial period.

It's hard to understand why most of the world hates Europeans (and by extension North Americans).