Today's plan is to hop a train for about an hour and 20 minutes and look for a specific monument in a field. One hopes that today I'll remember to put sunscreen on my face. It is, in fact, possible to get a sunburn in the UK in September.

Details and photos tonight.

A couple of streaks ended today.

First, the good one: after 221 days, I finally got to fly somewhere. That's the longest I've gone without traveling by air since 1980, or possibly earlier.

Second, the bad one: after 82 days, I finally missed 10,000 steps, owing to the above-mentioned flying. That's the longest stretch of 10k-plus days I've had since getting a Fitbit. (I would have made it, too, if it weren't for those meddling time zones.)

Finally, there is a crushing disappointment that I will share tomorrow morning. Well, maybe not crushing, but certainly disappointing. And temporary, it seems, but coinciding exactly with my trip here. So, boo.

Chicago-based writer Daniel Kay Hertz finds that reactions to gentrification, and its effects, have remained the same for over a century:

I’ve been struck by the Groundhog Day quality of thinking on these changes. Decade after decade, observers alternately wonder at the latest clique of young, middle-class white people to have chosen to live in a less privileged urban neighborhood, and then predict that clique’s imminent demise, a return to the “natural” order of things.

As early as the 1920s, the sociologist Harvey Zorbaugh quoted people who swore that time was up for the residents of Tower Town, Chicago’s bohemian answer to New York City’s Greenwich Village, as young artists abandoned it. (Many of those who left just settled a short walk up the lakefront in what we now call Old Town.) Zorbaugh himself was convinced that the Gold Coast, the last inner city stronghold of Chicago’s upper class, had barely ten years left before the rich realized they would have fewer headaches farther from the chaos of the downtown Loop. (A century later, the Gold Coast is still, well, Gold.)

Often, even the gentrifiers themselves don’t quite believe that what they’ve created can last. Into the 1970s—when parts of Lincoln Park had already become wealthier than many white-collar suburbs—a Lincoln Park neighborhood association director fretted that one wrong development might push the area towards a “ghetto.”

Why have we found it so hard to believe that a generations-old trend of growing affluence at the core of a major city could be durable? And why has it proven so durable?

Hertz provides some pretty compelling and well-researched answers.

Not only do the Great Lakes face threats from thirsty populations outside their basin, but they're also chock full of plastic microparticles:

One recent study found microplastic particles—fragments measuring less then 5 millimeters—in globally sourced tap water and beer brewed with water from the Great Lakes.

According to recent estimates, over 8 million tons of plastic enter the oceans every year. Using that study’s calculations of how much plastic pollution per person enters the water in coastal regions, one of us (Matthew Hoffman) has estimated that around 10,000 tons of plastic enter the Great Lakes annually. Now we are analyzing where it accumulates and how it may affect aquatic life.

Using our models, we created maps that predict the average surface distribution of Great Lakes plastic pollution. They show that most of it ends up closer to shore. This helps to explain why so much plastic is found on Great Lakes beaches: In 2017 alone, volunteers with the Alliance for the Great Lakes collected more than 16 tons of plastic at beach cleanups. If more plastic is ending up near shore, where more wildlife is located and where we obtain our drinking water, is that really a better outcome than a garbage patch?

Mmm. Plastic beer! Since most of the beer I drink comes from breweries walking distance from my house...yum!

After watching the Aral Sea disaster unfold in the second half of the last century, governors of the states and provinces around the Great Lakes formed a compact to prevent a similar problem in North America. Crain's looks at how well it's done for the past 10 years:

Hammered out over five years, the Compact, aimed at keeping Great Lakes water in the Great Lakes, was approved by the legislatures of all eight states bordering the Great Lakes, Congress and the Canadian provinces and signed into law by President George W. Bush on Oct. 3, 2008.

The Great Lakes Compact prohibits new or increased diversions outside the Great Lakes Basin with limited exceptions for communities and counties that straddle the basin boundary and meet rigorous standards. It asks states to develop water conservation plans, collect water use data, and produce annual water use reports. Great Lakes states as well as Ontario and Quebec are to keep track of impacts of water use in the basin.

Certainly, the future of water on the planet seems fraught enough to make one wonder how the Great Lake Compact will fare as the years pass. The most ardent supporters of the Compact say that challenges abound. These include a changing climate that is expected to bring drought as well as heightened political pressure to open up what some view as an invaluable public resource now off limits to the rest of the world.

So it is easy to see why the Great Lakes loom large in the eyes of those who seek to solve their water woes. The lakes are the largest system of fresh surface water on Earth. They hold 84 percent of North America's surface fresh water and about 21 percent of the world's supply, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

This will be one to watch. Being adjacent to Lake Michigan is one of the biggest reasons I'm optimistic about Chicago; but what if the shoreline were 20 kilometers away? It could happen.

The New York City subway, with its passive air exchange system and tunnels too small for active ventilation or air conditioning, have gotten excessively hot this summer:

On Thursday, temperatures inside at least one of the busiest stations reached 40°C—nearly 11°C warmer than the high in Central Park.

The Regional Plan Association, an urban planning think tank for the greater metropolitan area, took a thermometer around the system’s 16 busiest stations, plus a few more for good measure, and shared the data with CityLab. A platform at Union Square Station had the 40°C reading at 1 p.m., which was the hottest they found, although Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall and Columbus Circle weren’t far off at 39°C and 38½°C, at around 10 and 11 a.m., respectively. Twelve out of the 16 busiest stops boiled at or over the 32°C mark in the late morning and early afternoon.

One might think that subway stations would offer crisp respite to sweaty New Yorkers, being underground and all. But you’d be wrong. Heat doesn’t only “rise”—it just diffuses to cooler areas, which can include below-ground spaces. Plus, only a few of the city’s 472 stations are equipped with air conditioning; most rely on a passive ventilation system better known for their Marilyn Monroe moments above ground. This system was built in the days before AC, and the MTA says it’s not possible to squeeze the station-cooling machinery that other metro systems have inside New York’s narrow tunnels. Meanwhile, the units that cool passengers inside cars actually shed heat into the stations as trains pass through.

That onboard air-conditioning can fail, too. The MTA has also seen a rising number of complaints about overheated cars in recent years. In today’s issue of Signal Problems, his indispensable newsletter focused on subway accountability, the journalist Aaron Gordon reports that “about two percent of all subway cars in service on any given day might not have working A/C,” according to the MTA. That means at least 100 cars are roasting passengers on any given day this summer.

This problem also bedevils the London Underground.

Meanwhile, here in Chicago, we're having our 73rd day this year above 27°C, just 10 short of the record. Given the normal number of temperatures that warm between now and October, I think we'll probably set a new one.

And the sunlight here looks eerily orange and hazy today, because of climate change-driven wildfires out west.

Welcome to the future.

I love to travel. So I was surprised to learn, after chasing a hunch, that I haven't been outside the state of Illinois since January 22nd, 194 days ago. I confirmed this with Google Timeline.

The last time I've gone this long without traveling to another state (or country), as far as I can tell, was 3 August 1981 to 5 March 1982, a gap of 214 days. But my family probably went up to Wisconsin at some point during that period, so I can't exactly call that a reliable record. Same with the 213-day gap between 4 January 1979 and 5 August 1979 that's on the record. (These dates come from my mom's journals, which is why I'm not sure they're complete.)

So it's possible that this is the longest time in my entire life that I've gone without crossing a state line. And if I don't leave Illinois before my next scheduled trip on August 31st, that'll be 221 days, and absolutely a lifetime record.

What surprises me even more is that I didn't realize this until yesterday. Weird.

Sediment under Lake Chichancanab on the Yucatan Peninsula has offered scientists a clearer view of what happened to the Mayan civilization:

Scientists have several theories about why the collapse happened, including deforestation, overpopulation and extreme drought. New research, published in Science Thursday, focuses on the drought and suggests, for the first time, how extreme it was.

[S]cientists found a 50 percent decrease in annual precipitation over more than 100 years, from 800 to 1,000 A.D. At times, the study shows, the decrease was as much as 70 percent.

The drought was previously known, but this study is the first to quantify the rainfall, relative humidity and evaporation at that time. It's also the first to combine multiple elemental analyses and modeling to determine the climate record during the Mayan civilization demise.

Many theories about the drought triggers exist, but there is no smoking gun some 1,000 years later. The drought coincides with the beginning of the Medieval Warm Period, thought to have been caused by a decrease in volcanic ash in the atmosphere and an increase in solar activity. Previous studies have shown that the Mayans’ deforestation may have also contributed. Deforestation tends to decrease the amount of moisture and destabilize the soil. Additional theories for the cause of the drought include changes to the atmospheric circulation and decline in tropical cyclone frequency, Evans said.

What this research has to do with the early 21st Century I'll leave as an exercise for the reader.

When I get home tonight, I'll need to read these (and so should you):

And now, I'm off to the Art Institute.

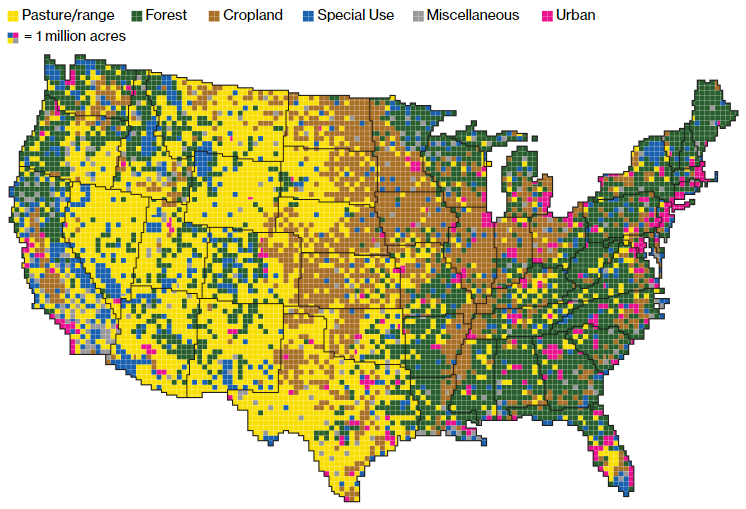

Bloomberg published on Monday a super-cool analysis of U.S. land use patterns:

Using surveys, satellite images and categorizations from various government agencies, the U.S. Department of Agriculture divides the U.S. into six major types of land. The data can’t be pinpointed to a city block—each square on the map represents 250,000 acres of land. But piecing the data together state-by-state can give a general sense of how U.S. land is used.

Gathered together, cropland would take up more than a fifth of the 48 contiguous states. Pasture and rangeland would cover most of the Western U.S., and all of the country’s cities and towns would fit neatly in the Northeast.

This is, of course, total Daily Parker bait.