The semi-annual Chicago Sunrise Chart is up. Enjoy.

Slate explains how Chicago's Deep Tunnel project has relieved the city of the worst effects of rainstorms—but just isn't adequate for the new, wetter climate:

The history of Chicago can be told as a series of escapes from wastewater, each more ingenious than the last. Before the Civil War, entire city blocks were lifted on hydraulic jacks to allow for better drainage, and the first tunnel to bring in potable water from the middle of Lake Michigan was completed in 1867. In 1900, engineers reversed the flow of the Chicago River to protect the city’s drinking water, shifting its fetid contents from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi, enraging the city of St. Louis (which sued, and lost) and, years later, making Chicago the single-largest contributor to the “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico. In 1955, the American Society of Civil Engineers declared the river reversal one of the seven engineering wonders of the United States, alongside such better-known undertakings as the Hoover Dam, the Empire State Building, and the Panama Canal.

“The [Metropolitan Water Reclamation District] designed a system of sewers, tunnels, and reservoirs for a city that doesn’t exist anymore,” says Karen Hobbs, a former deputy environmental commissioner in Chicago who oversaw the creation of the city’s climate plan and now works as a policy analyst at the National Resources Defense Council. Metropolitan Chicago is no longer the place it was in 1960. The weather isn’t what it was then either. It’s a cautionary tale for a time when climate change has the nation’s planners, scientists, and engineers contemplating enormous endeavors like storm surge barriers or more radical, long-term geoengineering schemes. It’s also a reminder that any project that spans six decades from commencement to completion will be finished in a different world than the one in which it was conceived.

“It’s a marvel,” Hobbs adds. “But we have this tendency in this country to think we can build our way out of stuff. And we can’t always build our way out.”

Belatedly, the city has started using porous pavement in alleys and encouraging other ways of keeping water out of the sewers.

In the last half 2018, I made a number of changes in my life that I had put off for years. I moved, got a new car, repaired my dog, and made a couple of changes in my personal life to clear a solid path for next year. What that will bring overall, I have no idea.

Every year at this time I post some statistics for comparison with previous years. In 2018:

- Travel was way, way down; in fact, I traveled less in 2018 than in any year since 1998, with the longest gap between trips (221 days) in my entire life. Overall, I took the fewest trips (7) on the fewest flights (11) to the fewest other countries (1) and states (7) than in any year since 1995. I did beat 2017's total flight miles (44,680 km this year against 31,042 km last year), but only because of three trips to London. (Side note: the Republican party shut down the US government during two of those trips.)

- I posted 518 times on The Daily Parker, up 62 from last year and 59 from 2016, and the best showing since 2013 (537). The A-to-Z challenge helped.

- Parker only got 133 hours of walks, significantly less than last year, principally because of his leg injury. Not to mention he's 12½, slowing down, and wants a nap, dammit.

- Fitbit steps didn't change much: 5,262,521 for the year, up 2% from last year. It was, however, my best year for steps since getting my first Fitbit in 2014. It also had my biggest stepping day ever.

- Reading went up just a tiny bit, from 17 to 24. One of my friends read over 100; I'm not going to be there until I take a year off from work. (I predict that will happen in the 2040s.)

The only resolution I have for 2019 is to bring all of these numbers up, but only slightly.

The island-nation of Kiritimati just became the first place in the world to enter 2019. Good on 'em.

People may have noticed the Daily Parker tradition of welcoming Kiritimati into the new year. On 30 December 1994, Kiritimati changed time zones from UTC-10 (Hawai'i time) to UTC+14 (ludicrous time), in part so they could become the first place in the world to start the 21st Century. Technically, it worked.

However, since the highest point on the small island (population 6,500) rises only 13 m above the Pacific, the country is completely vulnerable to climate-change-induced sea-level rise. It probably will not be the first place in the world to greet the 22nd century.

So, happy new year, Kiritimati! I hope you outlive me.

The Chicago Tribune's architecture critic does not like the current proposal for the new Lincoln Yards development and its nine 120 m–plus buildings:

It would be dramatically out of scale with its surroundings, piercing the delicate urban fabric of the city’s North Side with a swath of downtown height and bulk. It also would be out of character with its environs, more Anytown than Our Town.

And that’s what the debate over Lincoln Yards is really about — not just the zoning change the developers seek, which would reclassify their land from a manufacturing district to a mixed-use waterfront zone, but urban character.

What kind of city are we building? Who is it for? Does it have room for the small and the granular as well as the muscular and the monumental?

The 180 m towers that line South Wacker Drive barely make an impression because they exist in the shadow of the 442 m Willis Tower. Alongside Armitage and the rest of west Lincoln Park, a tower of that size is a monster.

Cities need to grow and change, but this is the sort of incongruous Dodge City growth you expect in Houston, a city infamous for its lack of zoning.

And it could have lasting consequences, likely worsening the traffic congestion that already plagues streets like Clybourn and North avenues.

I just read The Battle for Lincoln Park while in London this week. That book talked about the period from around 1930 to around 1970, when affluent white rehabbers east of Larrabee battled the less-affluent, mixed-ethnicity residents west of Larrabee for control over the character of the neighborhood. Both lost; large commercial developers won. Note to Blair Kamin: History does not repeat, but it does rhyme.

After an amazing dinner at One Aldwych this evening, I grabbed a book from my room* and headed down to my own hotel's bar. Between the two places I met people from Italy, Spain, Cape Verde (via Portugal), Germany, Russia, Poland, Sardinia (yes, a part of Italy), and Wales (yes, a part of the UK).

London has made itself over the past two decades into this kind of mixed, cosmopolitan, vibrant city. I hope it continues; Brexit could kill it. So I'm glad I'm visiting now while it's at peak international. (The $1.27-to-£1 exchange rate doesn't hurt either.)

More photos. First, it was the best of Thames, it was the worst of Thames (compare with this one):

Second, the other side of St Pauls, along with yours truly and a pint of Beavertown Brewery Neck Oil Session IPA, at Founder's Arms on the Queen's Walk:

Finally, one of the greatest cultural centers in modern Europe, the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden:

And now, as my body thinks it's just coming up on 4pm, I will take yet another walk. London is a beautiful city; there's little I like more than just exploring it.

*An excellent and personally-relevant history of urban "renewal" in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago called The Battle for Lincoln Park.

Just a quick post of articles I want to load up on my Surface at O'Hare:

Off to take Parker to boarding. Thence the Land of UK.

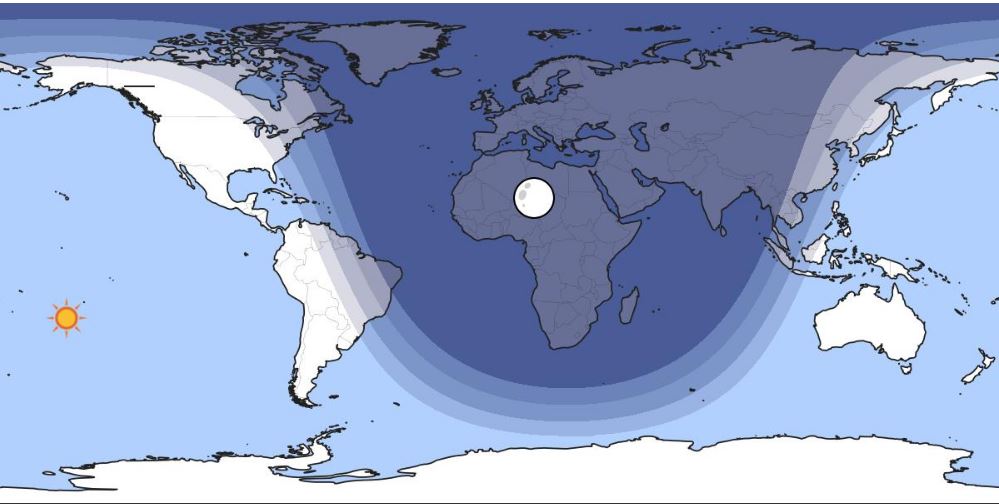

The December solstice happens today at 22:21 UTC, which is 16:21 here in Chicago, which it turns out is the exact time of tonight's sunset. This is also true for everywhere along the lightest gray line on this map:

Note also that Africa and Europe will have a brilliant gibbous moon at the same time.

Happy solstice!

President Trump took an entire motorcade from the White House to Blair House:

President Trump traversed a wide political chasm Tuesday evening when he personally welcomed George W. Bush, his occasional foil, to Blair House, the presidential guest quarters across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House.

But the actual distance was just 250 yards — a route Trump and his wife Melania traveled in the presidential parade limousine, with a motorcade of at least seven other vehicles.

White House aides declined to comment when asked why the Trumps chose to take a motorcade and whether it was related to security.

In her autobiography “Becoming,” former first lady Michelle Obama wrote that the Secret Service sometimes requested she or her husband “take the motorcade instead of walking in the fresh air” to Blair House for security reasons.

A search of Internet archives found at least six occasions when President Obama walked from the White House to Blair House. The search did not immediately find any times he took a motorcade, other than when he and Michelle left Blair House after spending the night on Inauguration Day in January 2009 and traveled to St. John’s Church for a prayer service.

Here's a satellite photo of the vast distance between the two buildings:

I can totally understand why he needed to drive.

CityLab describes new Daily Parker bait:

When a new rail or bus line gets built in the United States, its mere opening is often cause for celebration among transit advocates. That’s understandable, given the funding gaps and political opposition that often stymie projects.

But not all trains are bound for glory, and it’s often not hard to see why. In the new book, Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of U.S. Transit (Island Press, $40), Christof Spieler, a Houston-based transit planner, advocate, and former METRO board member, takes stock of the state of American transit with a tough-love approach. In nearly 250 pages of full-color maps, charts, and encyclopedia-style entries, Spieler profiles the 47 American metropolitan regions that have rail or bus rapid transit to show what works, what doesn’t, and why.

But a dunk-fest this is not. Spieler highlights several examples of cities that are often commonly described as transit failures, but where the data tells another story. “Though Los Angeles’ first rail system was gone by 1963, it left a city that is still friendly to transit,” he writes of the iconically car-oriented city. And who knew that Buffalo, New York, and Fort Collins, Colorado, have transit systems to admire? The former may have the shortest and most oddly configured light-rail system in the country, but as it turns out, “Metro Rail outperforms most of the light-rail lines in the United States,” Spieler writes. (It’s also laden with glorious public art, as CityLab’s Mark Byrnes recently noted.) And Fort Collins has top-quality BRT for its size.

So, do I waive the rule against buying more books until half of this shelf is empty? Or do I hold fast and get this book when it goes paperback in a year or two?