A student at the University of Cincinnati has filed a fascinating lawsuit against the school for discrimination in its enforcement of sexual misconduct:

Is it possible for two people to simultaneously sexually assault each other? This is the question—rife with legal, anatomical, and emotional improbabilities—to which the University of Cincinnati now addresses itself, and with some urgency, as the institution and three of its employees are currently being sued over an encounter that was sexual for a brief moment, but that just as quickly entered the realm of eternal return. The one important thing you need to know about the case is that according to the lawsuit, a woman has been indefinitely suspended from college because she let a man touch her vagina.

The event in précis, as summarized by Robby Soave of Reason magazine: “Male and female student have a drunken hookup. He wakes up, terrified she's going to file a sexual misconduct complaint, so he goes to the Title IX office and beats her to the punch. She is found guilty and suspended.”

By some kind of weird alchemy involving the sum of its parts, this strange little event manages to hit upon almost every troubling aspect of the way that these cases are interpreted and punished on the contemporary campus. It proceeds from the assumption that if two drunk college students make out, one of them—and only one of them—is a victim of the event. It resulted in a fairly common but extremely severe consequence meted on students found guilty of very minor offenses—banishment from the university until the complainant graduates. And it suggests how easily the system can be manipulated by a student with an alleged grudge.

I'm curious to see how this turns out. It seems hard to believe that I went to university during a brief, golden age when we were treated as adults. I served 5 semesters on the Student Judiciary Board and heard so many stories of ridiculous student behavior, and still managed to find them odious enough to ban the offenders from campus a handful of times. I fear for our children that they won't ever grow up, because their parents and institutions won't let them.

The Economist's Johnson column last week (which I just got around to reading tonight) took on verb conjugations in journalism:

On May 14th, as Palestinians massed at the Gaza Strip’s border, Israeli soldiers fired on them, killing around 60 people. Shortly afterwards, the New York Times tweeted: “Dozens of Palestinians have died in protests as the US prepares to open its Jerusalem embassy.” Social media went ballistic. “From old age?” was one incredulous reply. #HaveDied quickly became a hashtag campaign.

English and most other European languages have both an active voice (Steve kicked John) and a passive (John was kicked by Steve). Style manuals, including The Economist’s, generally deprecate the passive voice. It is longer, for one thing. For another, it is often found in heavy academic and bureaucratic prose. Inexperienced writers tend to over-use it.

But critics of the passive often confuse two different things: syntax and semantics. Syntax has to do with the mechanics of putting a sentence together. In Steve kicked John, Steve is the subject and John is the direct object. But in John was kicked by Steve, John is now the subject, even though he is still the kickee, and Steve is still the kicker.

So what the critics really meant is that the Times erred in using an intransitive verb.

I analyzed this not as an argument for a particular kind of prose, but as an argument for learning the vocabulary of the thing you want to criticize. Critics of the Times' headline aren't wrong; they're just arguing the wrong point. One can understand viscerally why the Times' headline got under the skin. But as in so much of life, people on one side argued feelings and people on the other argued correctness.

Until people hear what the opposition really wants to say—until people make an effort to hear it, I mean—we're going to keep talking past each other. That said, I want everyone to read Orwell right now.

Alexis Madrigal, closer to an X-er than a Millennial, rhapsodizes on how the telephone ring, once imperative, now repulses:

Before ubiquitous caller ID or even *69 (which allowed you to call back the last person who’d called you), if you didn’t get to the phone in time, that was that. You’d have to wait until they called back. And what if the person calling had something really important to tell you or ask you? Missing a phone call was awful. Hurry!

Not picking up the phone would be like someone knocking at your door and you standing behind it not answering. It was, at the very least, rude, and quite possibly sneaky or creepy or something. Besides, as the phone rang, there were always so many questions, so many things to sort out. Who was it? What did they want? Was it for … me?

There are many reasons for the slow erosion of this commons. The most important aspect is structural: There are simply more communication options. Text messaging and its associated multimedia variations are rich and wonderful: words mixed with emoji, Bitmoji, reaction gifs, regular old photos, video, links. Texting is fun, lightly asynchronous, and possible to do with many people simultaneously.

But in the last couple years, there is a more specific reason for eyeing my phone’s ring warily. Perhaps 80 or even 90 percent of the calls coming into my phone are spam of one kind or another. Now, if I hear my phone buzzing from across the room, at first I’m excited if I think it’s a text, but when it keeps going, and I realize it’s a call, I won’t even bother to walk over. My phone only rings one or two times a day, which means that I can go a whole week without a single phone call coming in that I (or Apple’s software) can even identify, let alone want to pick up.

Meanwhile, robocalling continues to surge, with a record 3.4 billion of them sent in April—approximately 40% of all calls placed that month by some reckonings.

Welcome to the 21st century, where your 19th-century technologies do more harm than good.

Not all of this is as depressing as yesterday's batch:

I'm sure there will be more later.

Every so often I like to revisit old photos to see if I can improve them. Here's one of my favorites, which I took by the River Arun in Amberley, West Sussex, on 11 June 1992:

The photo above is one of the first direct-slide scans I have, which I originally published here in 2009, right after I took this photo at nearly the same location:

(I'm still kicking myself for not getting the angle right. I'll have to try again next time I'm in the UK.)

Those are the photos as they looked in 2009. Yesterday, during an extended internet outage at my house, I revisited them in Lightroom. Here's the 1992 shot, slightly edited:

And the 2009 shot, with slightly different treatment:

A side note: I did revisit Amberley in 2015, but I took the path up from Arundel instead of going around the northern path back into Amberley as in 2009, so I didn't re-shoot the bridge. Next time.

The Apollo Chorus is joining Northwestern University's Bienen School of Music this weekend in two performances of Rachmaninov's The Bells. Thus, no real blog post today.

But if you're in Chicago, swing by the Pritzker Pavilion at Millennium Park at 6:30pm for our free concert.

Darryl Fears, writing for the Washington Post today, highlights a new study that explains why coyotes have adapted so well to human environments:

As mountain lions and wolf packs disappeared from the landscape, coyotes took advantage, starting a wide expansion eastward at the turn of the last century into deforested land that continues today.

For reasons biologists do not quite understand, coyotes prefer open land over forest. It could be that bigger predators that kill them over territory and competition for food could better sneak up on them in forests, [Roland Kays, a research associate professor at North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences] theorized. But now, cameras have caught coyotes in forests where the apex predators have largely been removed, opening the prospect that coyotes could continue to move into territories where they have never been, such as into South America.

Unlike mountain lions, wolves and bears that were hunted to near-extinction in state-sponsored predator-control programs, coyotes do not give in easily, Kays said. “Coyotes are the ultimate American survivor. They have endured persecution all over the place. They are sneaky enough. They eat whatever they can find — insects, smaller mammals, garbage,” he said.

I've reported on coyotes before, in part because I'm happy they've found a home in Chicago. I've even seen them on my street, no more than 50 meters away from me.

The Cook County Forest Preserve District has some FAQs on coyotes, including what to do if one takes an interest in you.

A Swedish psychologist has preliminary data that suggest sleeping in on the weekends can make up for some sleep loss during the week, maybe:

Sleeping in on a day off feels marvelous, especially for those of us who don't get nearly enough rest during the workweek. But are the extra weekend winks worth it? It's a question that psychologist Torbjorn Akerstedt, director of the Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University, and his colleagues tried to answer in a study published Wednesday in the Journal of Sleep Research.

Akerstedt and his colleagues grouped the 38,000 Swedes by self-reports of sleep duration. Short sleepers slept for less than five hours per night. Medium sleepers slept the typical seven hours. Long sleepers, per the new study, snoozed for nine or more hours.

The researchers further divided the groups by pairing their weekday and weekend habits. Short-short sleepers got less than five hours a night all week long. They had increased mortality rates. Long-long sleepers slept nine or more hours every night. They too had increased mortality rates.

The short-medium sleepers, on the other hand, slept less than five hours on weeknights but seven or eight hours on days off. Their mortality rates were not different from the average.

Personally, getting 9 hours seems like a luxury. But I haven't been getting 7 enough lately. I have a dream that someday I will have a full week of 7+ hour nights again. I last had this happen in January.

On 13 May 1998, just past midnight New York time, I posted my first joke on my brand-new braverman.org website from my apartment in Brooklyn.

My first website of any kind was a page of links I maintained for myself starting in April 1997. Throughout 1997 and into 1998 I gradually experimented with Active Server Pages, the new hotness, and built out some rudimentary weather features. That site launched on 19 August 1997.

By early April 1998, I had a news feed, photos, and some other features. On April 2nd, I reserved the domain name braverman.org. Then on May 6th, I launched a redesign that filled out our giant 1024 x 768 CRT displays. Here's what it looked like; please don't vomit:

On May 13th, 20 years ago today, I added a Jokes section. That's when I started posting things for the general public, not just for myself, which made the site a proto-blog. That's the milestone this post is commemorating.

Shortly after that, I changed the name to "The Write Site," which lasted until early 2000.

In 1999, Katie Toner redesigned the site. The earliest Wayback Machine image shows how it looked after that. Except for the screenshot above, I have no records of how the site looked prior to Katie's redesign, and no easy way of recreating it from old source code.

I didn't call it a "blog" until November 2005. But on the original braverman.org site, I posted jokes, thoughts, news, my aviation log, and other bits of debris somewhat regularly. What else was it, really?

Today, The Daily Parker has 6,209 posts in dozens of categories. Will it go 20 more years? It might. Stick around.

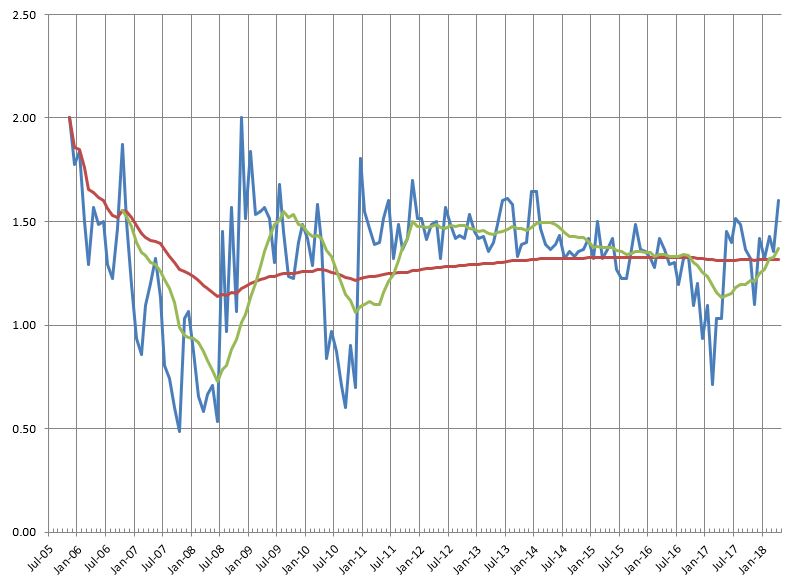

This month will see two important Daily Parker milestones. This is the first one: the 6,000th post since braverman.org launched as a pure blog in November 2005. The 5,000th post was back in March 2016, and the 4,000th in March 2014, so I'm trucking along at just about 500 a year, as this chart shows:

Almost exactly four years ago I predicted the 6,000th post would go up in September. I'm glad the rate has picked up a bit. (New predictions: 7,000 in May 2020 and 10,000 in April 2026.)

Once again, thanks for reading. And keep your eyes peeled for another significant Daily Parker milestone in a little less than two weeks.